Managing Difficult People in Academia: Lessons from Pakistan's Ivory Towers

Posted 7 months ago

If you've ever worked in a university setting in Pakistan, you've likely uttered something like, "He's impossible to work with" or "She always creates drama in meetings." In academia, where egos are sharp and hierarchies entrenched, managing difficult people is not just an HR issue; it's a leadership imperative. Yet the question remains: Are these individuals truly difficult, or are we misinterpreting challenging behavior as a reflection of difficult people?

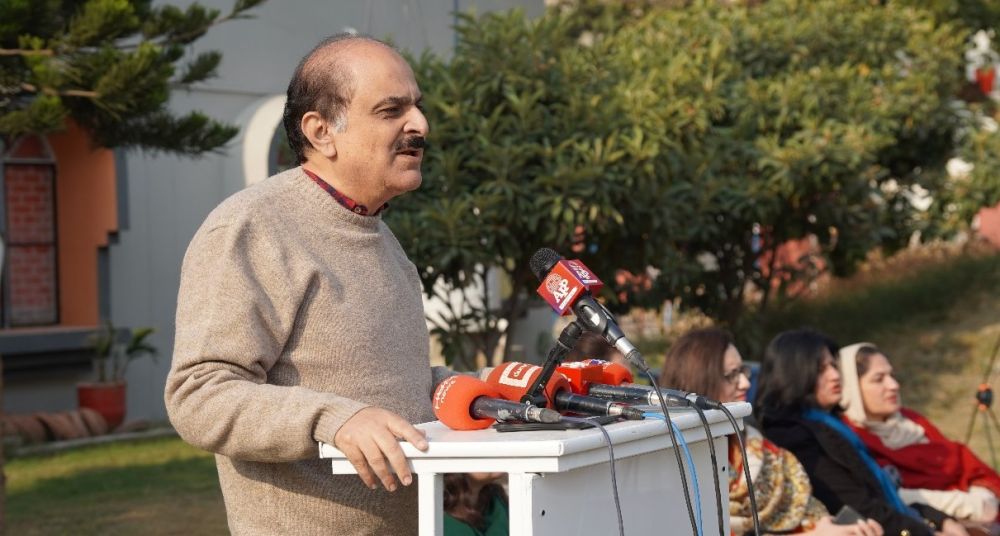

Professor Dr. Muhammad Mukhtar, a seasoned academic leader and founding Vice Chancellor of the four universities in Pakistan, offers a compelling perspective. "In Pakistani academia, we often personalize behavior rather than contextualize it. It's essential to separate the person from the problem," he says. This philosophy becomes a cornerstone for managing interpersonal friction in universities, where politics and pedagogy often collide.

Shifting the Lens: From Labels to Behaviors

The first step in transforming a toxic work environment is to change the language. Labeling someone as "difficult" seals them into a role they may not even recognize. Instead, Dr. Mukhtar advocates describing the observable behavior. Consider the difference between saying, "Dr. A is so negative," versus, "Dr. A tends to highlight issues without suggesting alternatives during departmental meetings." This reframing allows space for conversation, not condemnation.

In a society like Pakistan's, where hierarchy often supersedes dialogue, such nuance can change the culture of an academic institution. It's not about sugarcoating reality. It's about fostering clarity and preserving dignity.

Trigger Points and Emotional Management

In Pakistani institutions, many senior faculty members have risen through the ranks over the course of decades of service. Emotions run high when promotions, projects, or policy changes are involved. Understanding one's emotional triggers becomes paramount.

The strategy? Acknowledge your internal reaction, identify the behavior that caused it, and prepare a proactive response. For instance, if a senior professor undermines your idea in a curriculum meeting, notice your clenched jaw or racing pulse. Then, instead of reacting defensively, take a breath and respond with, "I'd like to reflect on your feedback and follow up after giving it some thought."

Emotional intelligence is not about appeasement; it's about empowerment and control. Understanding and managing your emotional triggers in the face of challenging behavior is a powerful tool in your leadership arsenal.

The Academic "Energy Filter"

Not every behavioral hiccup requires your intervention. A proper filter to apply is:

- Is it impacting your work?

- Is it a recurring issue?

- Do you influence it or you get influenced by it?

A colleague's constant complaints about university policies may be irritating, but unless they are affecting performance or morale, they may not warrant action. Academic leaders must choose their battles lest they burn out on micro-conflicts while the institution drifts into mediocrity.

Building Trust With Your Employees Before It's Needed

Pakistani academia thrives on relationships. Whether it's collaborations, research grants, or departmental decisions, trust is currency. Dr. Mukhtar emphasizes the need to "invest in trust capital before the conflict account is overdrawn." His advice? Start every meeting with a brief personal check-in, publicly acknowledge colleagues' contributions, and follow through on commitments.

Trust isn't built during conflict. It's built in the quiet moments of consistency and respect. By investing in trust capital before the conflict account is overdrawn, you can foster a sense of security and value in your academic relationships.

The "Both-And" Model for Conflict

Adopting a collaborative mindset is not about enforcing rigid compliance. It's about ensuring that everyone's needs and realities are heard and considered. By proposing solutions that acknowledge both institutional needs and departmental realities, you can make your team feel included and heard.

Strength in Strategic Support Networks

Managing difficult individuals doesn't mean going it alone. Establish a three-tiered support system:

- A sounding board: Someone who listens, preferably outside your direct work circle.

- A problem-solver: A mentor or peer with experience navigating university politics.

- An institutional ally: HR personnel or higher-ups who understand the formal protocols.

In Pakistan, where institutional frameworks are evolving and leadership roles are sometimes influenced, such a network isn't just helpful—it's essential.

Accountability Starts with You

Leaders who model accountability inspire it. Dr. Mukhtar often reminds young faculty that "owning your part in a conflict isn't weakness; it's leadership." By saying, "I could have communicated this more clearly," you invite the other party to mirror your honesty. In a culture where saving face often takes precedence over solving problems, this humility is revolutionary.

A Culture of Collaborative Change in Academia

Managing difficult people is less about confrontation and more about calibration. In the Pakistani academic landscape, rich in talent yet tangled in tradition, leaders must lead with both clarity and compassion. Dr. Mukhtar's insight encapsulates this duality: "Our universities should not just be factories of knowledge but ecosystems of mutual respect."

By reframing behaviors, regulating responses, and investing in relationships, we can transform our ivory towers into pleasant environments and professional harmony.

Additional Thoughts by Scholars

According to Dr. Wasim Sajjad, Fulbright Scholar UW Madison, USA "It's a thoughtful piece. From my experience, even when raising issues with the intention of constructive dialogue and mutual solutions, responses can sometimes be personal rather than professional. In academic settings, hierarchical structures often limit direct communication with top management, and it's expected that concerns be raised through departmental heads. However, I believe individuals are best positioned to explain their own cases when they have the relevant knowledge. Interestingly, it’s often the middle management that resists open discussions, sometimes shaping the narrative before others have a chance to present their side. Out of respect for seniority or to avoid conflict, many voices go unheard."